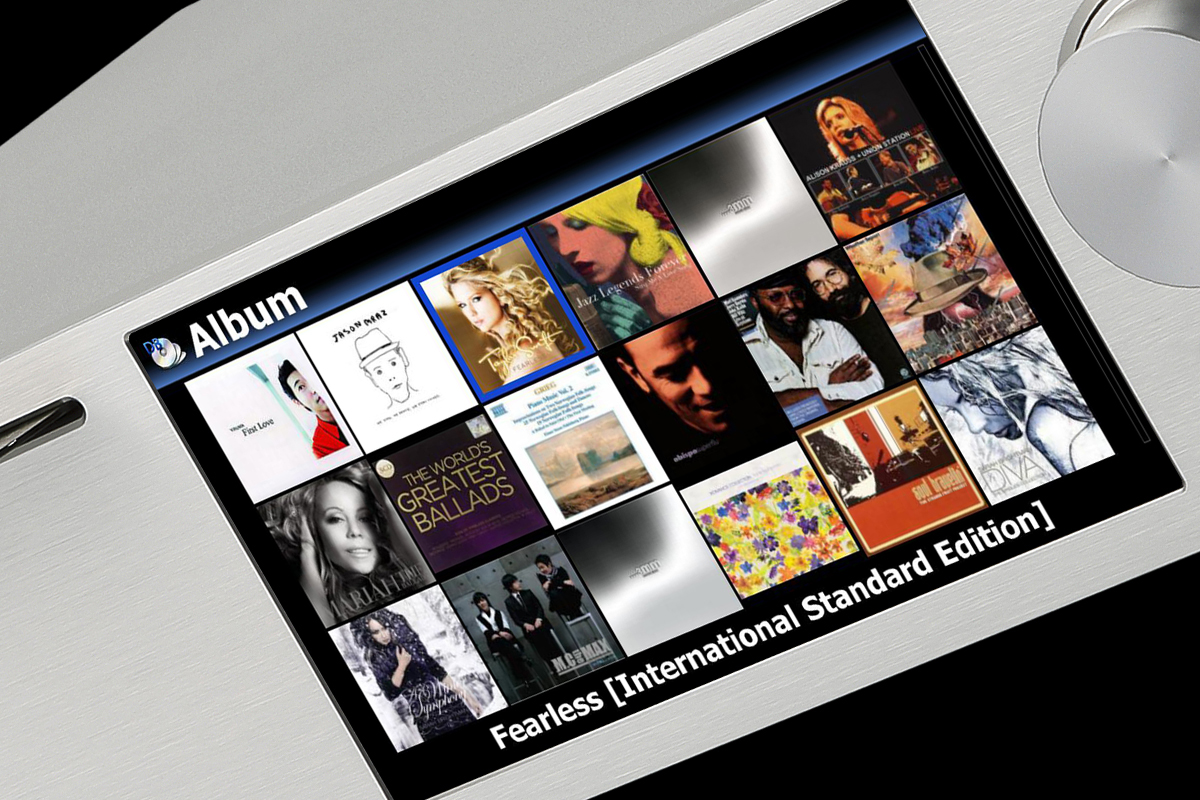

When the Hong Kong–based digital-audio brand AURALiC stopped answering emails in September 2025, the silence spoke volumes. The community forum vanished without explanation. Dealers couldn’t reach anyone. The website went dark except for a terse notice about suspended US shipments. For owners of AURALiC’s Altair, Aries, and Vega streamers, each costing thousands of dollars, the reality set in quickly: they were holding expensive hardware without a support lifeline and facing an uncertain future.

I’ve listened to AURALiC gear in friends’ systems over the years. The build quality always impressed me. Solid-aluminum casework, pristine sound. These weren’t throwaway products. Yet here we are, with the company effectively shuttered and customers wondering how long their streamers will remain functional, as streaming services continue to update their application programming interfaces (APIs), and protocols inevitably drift out of sync.

AURALiC’s apparent collapse was actually a slow bleed. Founder Xuanqian Wang stepped down in January 2025 to pursue “other ventures and race sports cars” while maintaining his ownership stake. By mid-September, the online forum vanished. Then distributors confirmed what everyone suspected: sales had plummeted 80% in 2025, driven by tariff conflicts, intensifying competition from budget streamers, and difficult global economic conditions. The company ceased operations.

AURALiC wasn’t alone. Cocktail Audio, a Korean manufacturer known for its music servers and streamers, quietly folded around the same time. Cocktail’s parent company, Novatron, had attempted to move upmarket into expensive “elite” products, but this may have alienated its core customer base. Its website went offline in November 2024, leaving owners stranded with devices that will also slowly become obsolete as firmware ages and streaming APIs evolve.

Two companies, similar trajectories, same endpoint. Are we watching the beginning of a broader shakeout in streaming hardware? And what does this mean for the category going forward?

Tariff trap

Let’s start with the obvious. Earlier in 2025, AURALiC suspended all US shipments, citing “US government tariff policy.” For a premium audio brand, losing the American market isn’t just a pain—it’s existential. The US is one of the primary markets for high-end audio equipment. Cut that off, and revenue models collapse.

The timing was brutal. Just as AURALiC faced mounting software-development costs and increasing competition from budget alternatives, it lost the ability to sell into its most important market. While European markets remained stable, sales declines in the US and China proved critical.

But tariffs don’t explain everything. Plenty of audio companies have faced trade barriers and survived. Tariffs accelerated AURALiC’s decline, but they didn’t create the underlying vulnerabilities.

The software quicksand

Here’s the fundamental problem with networked streamers: they’re essentially computers masquerading as audio components. A good amplifier or DAC, once designed and manufactured, requires minimal ongoing development. Fix any bugs, maybe release a firmware update or two, then move on to the next product. The hardware does what it says, and, if built well, it usually keeps going for decades.

Audio streamers are different. Every streaming service updates its API periodically. Spotify changes authentication methods. Tidal tweaks protocols. Qobuz rolls out new features. Roon updates its integration requirements. Each change means engineering work for the manufacturers of streaming components. Someone needs to update your streamer’s software to maintain compatibility, test it, push it out to customers, and troubleshoot issues.

This creates a trap in the form of ongoing labor. The hardware is sold once, but manufacturers have to commit to ongoing software support, indefinitely. Or at least for as long as customers reasonably expect their expensive streamers to function, which in high-end audio is measured in years, or possibly even decades.

What happens in reality is that companies release streamers with great fanfare, robust feature sets, and premium pricing. Then software updates slow to a crawl. New services take months or years to integrate. Bugs linger. Eventually, the company either can’t afford the ongoing engineering costs or decides the returns don’t justify the investment. Customers get frustrated. The brand’s reputation erodes. Sales decline. The cycle accelerates.

AURALiC fell into this trap. While functional, its Lightning DS app never achieved the polish of its competitors. Software updates became sporadic. Customer complaints about connectivity issues and missing features piled up on forums. The company clearly struggled to keep pace with the software side of the business, even as it continued producing excellently engineered hardware.

The economics of this business are a massive challenge for such small, specialized companies. A streamer sold in 2020 generated zero revenue after the initial sale, but required ongoing software maintenance through 2025 and beyond. Unless there’s an accompanying software ecosystem with recurring revenue, or there’s massive scale to spread development costs across thousands of units, the math eventually breaks down.

The crush of commoditization

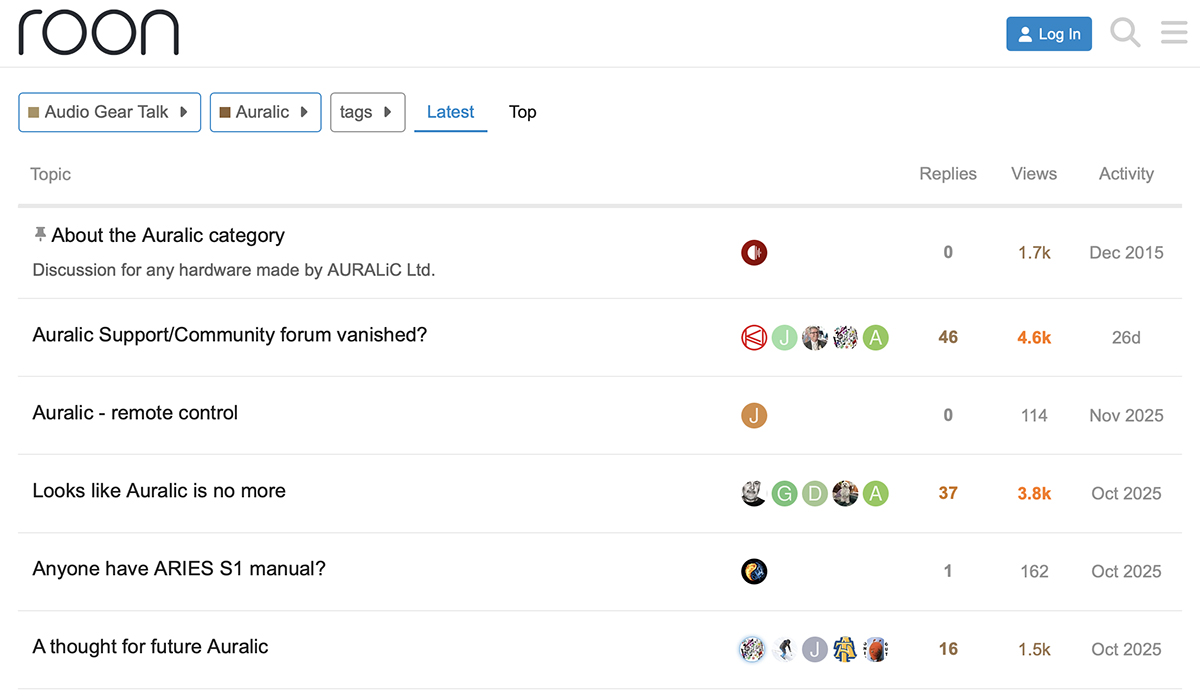

While AURALiC struggled with software costs, the market was transforming. When the company first launched, building a quality network streamer required specialized expertise and commanded premium pricing. Today, you can buy capable streamers for a fraction of what AURALiC’s products cost.

Take the many products we’ve reviewed here recently at SoundStage! Simplifi. The WiiM Ultra, tested in May 2025, costs US$329 and delivers a staggering feature set: touchscreen interface, room correction, subwoofer management, comprehensive streaming-service support, Roon Ready certification, and a capable, well-implemented ESS Sabre DAC. For many, it’s indistinguishable from streamers costing ten times as much.

![]()

The Bluesound Node Icon, reviewed in June 2025, takes the middle ground at US$1199. It uses dual ESS ES9039Q2M Sabre DACs in a mono configuration and has THX AAA headphone amplification, balanced XLR outputs, and BluOS software, which is mature and stable. Premium materials and engineering, as well as ecosystem integration, justify the increased cost. But its price is still a fraction of what AURALiC’s flagship products commanded.

Even the budget Bluesound Node Nano, which we reviewed last September and now costs US$379, packs the same ESS ES9039Q2M DAC as its more expensive siblings and delivers solid performance for casual listening.

This commoditization of audio products stems from several factors. Chip manufacturers now offer system-on-chip solutions that integrate streaming capabilities, network connectivity, and audio processing in single, inexpensive packages. Manufacturing in Asia has continually driven costs down. And brands like WiiM, operating with different margin expectations and targeting volume over profit per unit, have flooded the market with competent, attractively priced alternatives.

For AURALiC, this created an impossible situation: the need to justify price premiums of thousands of dollars over budget alternatives. Old audiophile arguments about better power supplies, superior component selection, and optimized circuit design become harder to defend when budget streamers sound genuinely good and measurable differences are marginal.

The market for ultra-premium streaming hardware is finite and shrinking. As budget options improve, the value proposition narrows to an increasingly small demographic willing to pay vast premiums for incremental improvements. That’s a shaky foundation for sustaining a business, especially when simultaneously bleeding cash on software development.

The ecosystem advantage

Perhaps the most telling aspect of the current market is which companies are thriving. It’s not the ones selling premium standalone streamers; it’s the ecosystem builders.

Lenbrook International’s BluOS platform runs across multiple products from multiple brands—not just Bluesound, NAD, and PSB, all of which are owned by Lenbrook, but also Monitor Audio, DALI, and Cyrus. The software-development costs are spread across a much larger installed base.

When we reviewed the Cambridge Audio EXN100, we noted the continuously evolving feature set of its StreamMagic platform. Cambridge Audio can sustain that development because it sells amplifiers, speakers, and other components alongside its streamers, attracting customers across multiple product categories.

Even integrated amplifiers with streaming capabilities make more economic sense than standalone streamers. The Eversolo Play (US$699), which I reviewed in September 2025, combines streaming, DAC, and amplification in one box, making it a complete “simplifi’d” solution. The company justifies the price point by delivering incredible functionality. The value equation shifts in its favor.

Companies like Sonos and WiiM operate on entirely different business models. Sonos sells complete multiroom ecosystems. Once you’ve invested in several Sonos speakers, you’re effectively locked into its platform. WiiM keeps operational costs incredibly lean, uses aggressive pricing to drive volume, and is now expanding into powered speakers and integrated amplifiers rather than pure streamers.

Pure-play premium streaming-hardware companies are probably in the worst possible position, competing against better-funded ecosystem players and ultra-cheap commodity alternatives while bearing the full weight of perpetual software-development costs. It’s hard to envision a sustainable business model in that space.

What survives?

Not all streaming hardware is doomed. But the category is consolidating around specific models. Budget streamers with lean operations and realistic margin expectations will persist. WiiM, for example, demonstrates that streaming hardware remains viable at accessible price points when costs are controlled aggressively, and it doesn’t try to compete on premium positioning. Its products work well, are priced to move volume, and, while features are continuously being added, don’t promise more than they can deliver.

Mid-tier streamers from established brands with broader product lines can also survive. Bluesound, Cambridge Audio, NAD, and Rotel all benefit from diversification and established dealer networks.

Premium streamers with genuine technical differentiation might carve out small niches. Products with advanced room correction like Dirac Live, sophisticated DSP capabilities, or integration with professional audio workflows can justify higher prices to specific customers. But the market remains small.

All-in-one solutions will grow. Streaming integrated amplifiers, powered speakers with network connectivity, and complete wireless speaker systems like the Devialet Phantom Ultimate make more sense for most buyers than component separates. They reduce box count, simplify setup, and align with how most people actually want to consume music.

Boutique manufacturers selling expensive, single-purpose streamers with inadequate software resources and narrow product lines are going to have a hard time. Companies pursuing that model will face the same structural challenges that ended AURALiC and Cocktail Audio. Some will limp along. Others will fold. A few might get acquired for their customer base or intellectual property, though rumors suggest AURALiC’s IP might be available for around US$2 million, which tells you how little value the market assigns to orphaned streaming technology.

Both companies faced the same fundamental challenge: selling products in a category being simultaneously commoditized from below and squeezed by ecosystem players from above. The walls were closing in. They needed to either move up in genuine technical differentiation, move down to commodity pricing, or move sideways into broader ecosystems. They did none of these things successfully.

AURALiC’s products were well built, thoughtfully designed, and excellent-sounding. In a different world, that would have been enough. But we don’t live in that world anymore. The streaming-hardware business rewards scale, software excellence, and ecosystem integration. Technical competence in hardware design has become table stakes rather than a differentiator.

AURALiC’s and Cocktail Audio’s customers own devices that will become obsolete a lot sooner than they would have with ongoing support. Streaming services will update their APIs, protocols will drift out of sync, and with time the hardware will lose functionality, eventually leaving just a digital file player.

European distributors point out that AURALiC products, being relatively open in design with accessible parameters via web interfaces and supporting standards like Roon Ready, are better positioned for long-term usability than some alternatives. That’s true to a point. But when services update their authentication methods or change protocols, open standards only help if someone maintains the software. No one’s officially maintaining AURALiC’s software anymore.

Lessons for buyers

If you’re shopping for streaming hardware, the AURALiC collapse offers some instructive guidance. First, consider a company’s long-term viability. Small, undiversified companies carry inherent risks. A premium streamer is only valuable if it continues receiving updates and support. Betting on boutique manufacturers with narrow product lines is risky business, unfortunately.

Second, recognize that expensive doesn’t necessarily mean better or more sustainable. Budget streamers from established companies often offer better long-term value than boutique products from precarious manufacturers. The US$329 WiiM Ultra will likely receive software updates longer than many failed premium streamers, because WiiM has volume, momentum, and a sustainable business model.

Third, consider software dependency. These aren’t traditional audio components that function indefinitely once manufactured. They require ongoing maintenance to remain compatible with evolving services and protocols. Choose products from companies with demonstrated long-term software support and the resources to sustain it.

Lastly, consider ecosystem integration. Products supporting multiple services and protocols offer more future-proofing than those locked to proprietary systems. Roon Ready certification, wide streaming-service support, and open standards provide flexibility if your preferred hardware loses software support.

What’s next?

The streaming-hardware market is evolving. As is the way in hi‑fi, we’ll see continued consolidation. More small companies will fail or get acquired. Larger brands will dominate the remaining market. Budget options will keep improving, pushing premium products into smaller niches.

For consumers, this evolution presents both opportunities and challenges. On the positive side, capable streaming hardware is more affordable and accessible than ever. There are a number of brands that make excellent streaming integrated amplifiers that combine multiple functions in a single box.

All-in-one streaming systems will gain share at the expense of separate components. Most people don’t want a separate streamer, DAC, preamp, and amplifier. They want elegant systems that work seamlessly. Companies offering that will thrive. Single-purpose components will likely struggle.

Ecosystem integration will separate winners from losers. Products that work with Roon, support all major streaming services, and integrate with smart-home platforms have more value than isolated devices. Companies building walled gardens better have compelling reasons for customers to stay inside those walls.

Companies that master both hardware and software, or find ways to monetize ongoing software development, will survive. Those treating software as an afterthought will fail.

The companies heeding this warning will survive and potentially thrive. Those ignoring it will join AURALiC and Cocktail Audio in the audio industry’s expanding graveyard of failed streaming-hardware makers. The next few years will reveal which category each remaining company falls into.

As for current AURALiC owners, the situation remains uncertain. European distributors are working together to ensure continued service for existing customers and are preparing spare units to handle warranty cases. How long that support lasts and how effective it proves remains to be seen.

The party’s over for pure-play premium streaming-hardware makers operating in isolation. Companies can accept that reality and adapt, or they can insist the market is wrong and follow AURALiC into irrelevance. I suspect we’ll see more of both in the years ahead.

. . . AJ Wykes