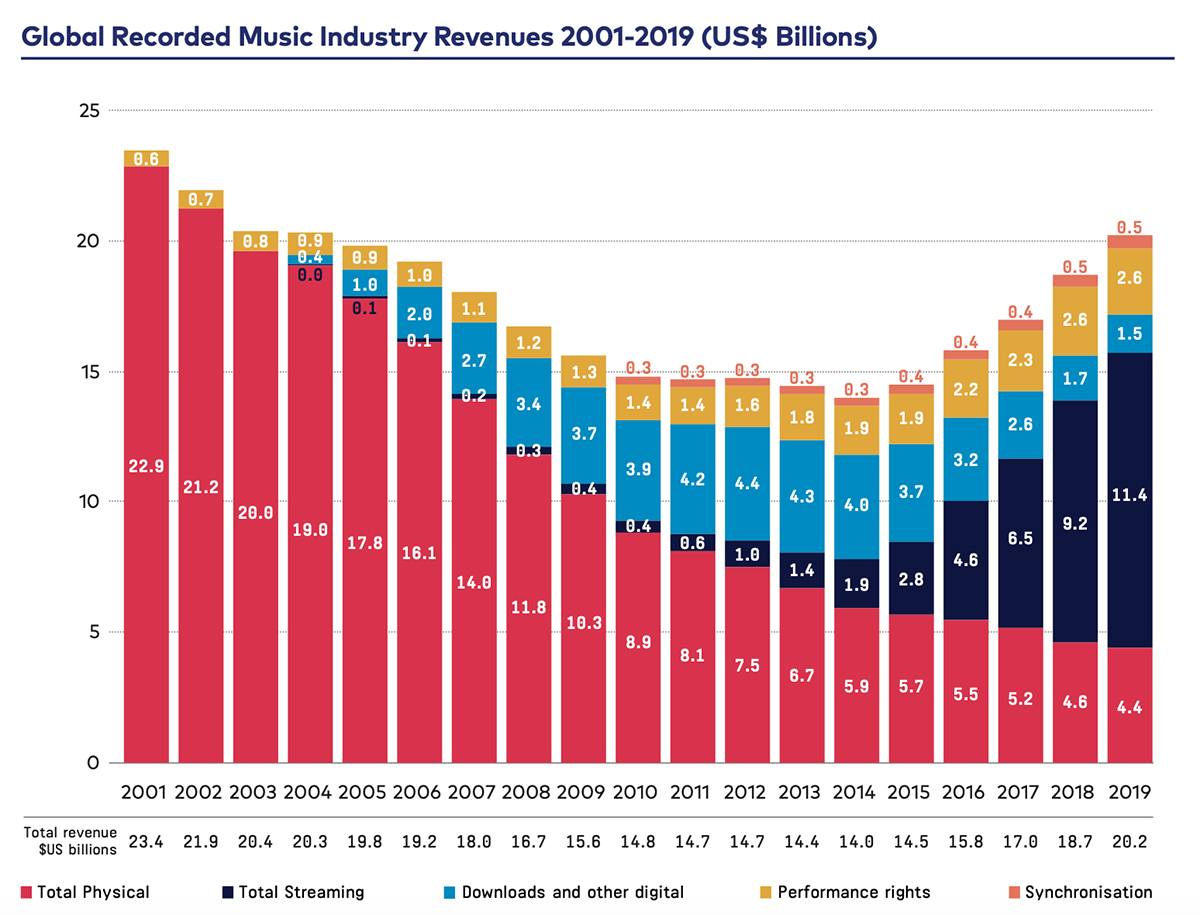

In the last decade, recorded music has undergone a sea change -- it has become disembodied. From the late 19th to the early 21st century, music was distributed on physical media. In the early 21st century, digital downloads held sway, then quickly gave way to on-demand streaming.

Last year, for the first time ever, streaming accounted for more than half of worldwide music-industry revenues, according to the 2019 Global Music Report of the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI). Worldwide streaming revenues in 2019 were $11.4 billion (all figures USD), 22.9% higher than in 2018 and representing 56.1% of the total market. Downloads were down 15.3%, and accounted for only 5.9% of music-industry revenues. Physical media sales were down 5.3%, and accounted for 21.6% of the total market.

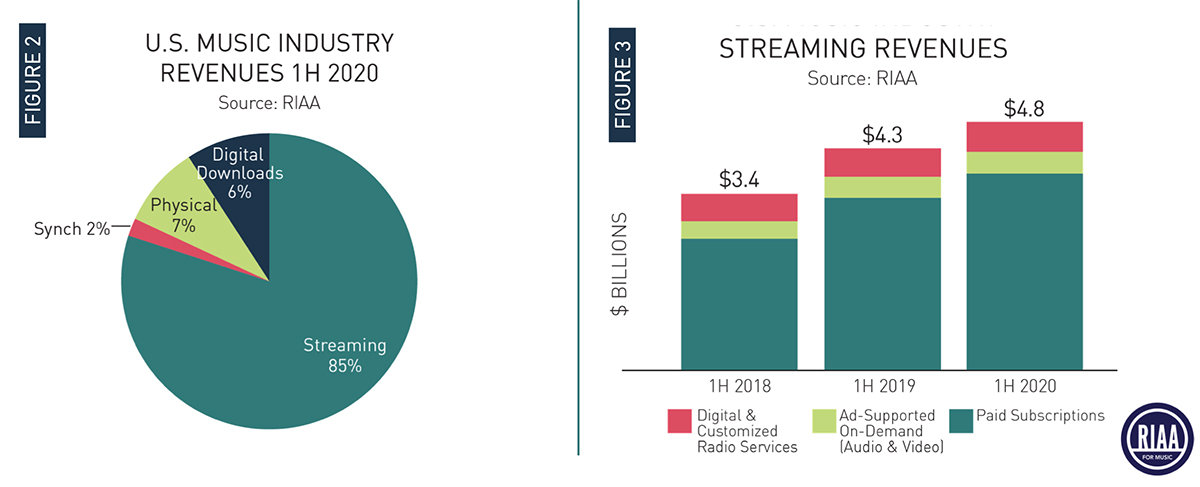

In the US, streaming has become even more entrenched, while sales of downloads and CDs have cratered. According to the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), US music-industry revenues from streaming during the first half of 2020 were $4.8 billion -- 12% higher than in the same period a year earlier. Streaming accounted for 85% of music-industry revenue during that period. Physical media accounted for 7%, digital downloads for 6%.

One exception to this trend is vinyl; but while vinyl sales are growing, they still represent only a tiny portion of overall revenues. According to IFPI, worldwide sales of LPs grew 5.3% in 2019 but accounted for only 3.5% of total revenues. In the US, vinyl sales were up 3.6% in the first half of 2020 compared to the same period in 2019, according to the RIAA -- and accounted for 4.1% of revenues.

The disembodiment of music means that, for most people, software has become a critical component of the listening experience. That software might be a mobile or desktop app from a streaming service, or a proprietary app from an audio manufacturer.

Interacting

According to the market-research firm Statista, the two leading music services are Spotify, with 138 million paid subscribers, and Apple Music, with 68 million paid subscribers. Spotify gets high praise from users and reviewers for its social features and discovery tools, such as customized Discover Weekly playlists, which are based on each user’s listening habits, and those of other users with similar tastes. An advantage of Apple Music is the way it integrates streamed music with local iTunes libraries.

Like most streaming services, Spotify and Apple both use lossy compression. More interesting to audiophiles are the services that offer lossless CD-resolution and high-resolution music. These services include Amazon Music HD, Qobuz, and Tidal, as well as two services that specialize in classical music -- Idagio and Primephonic.

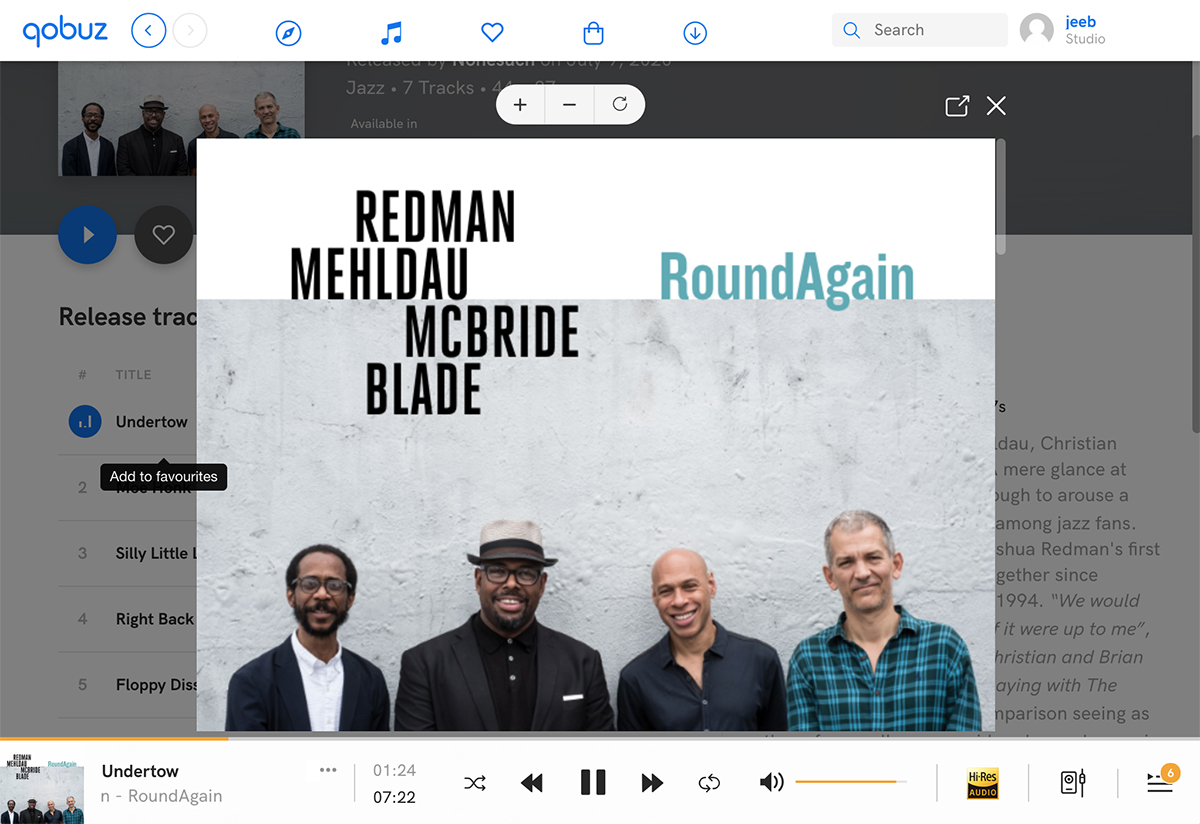

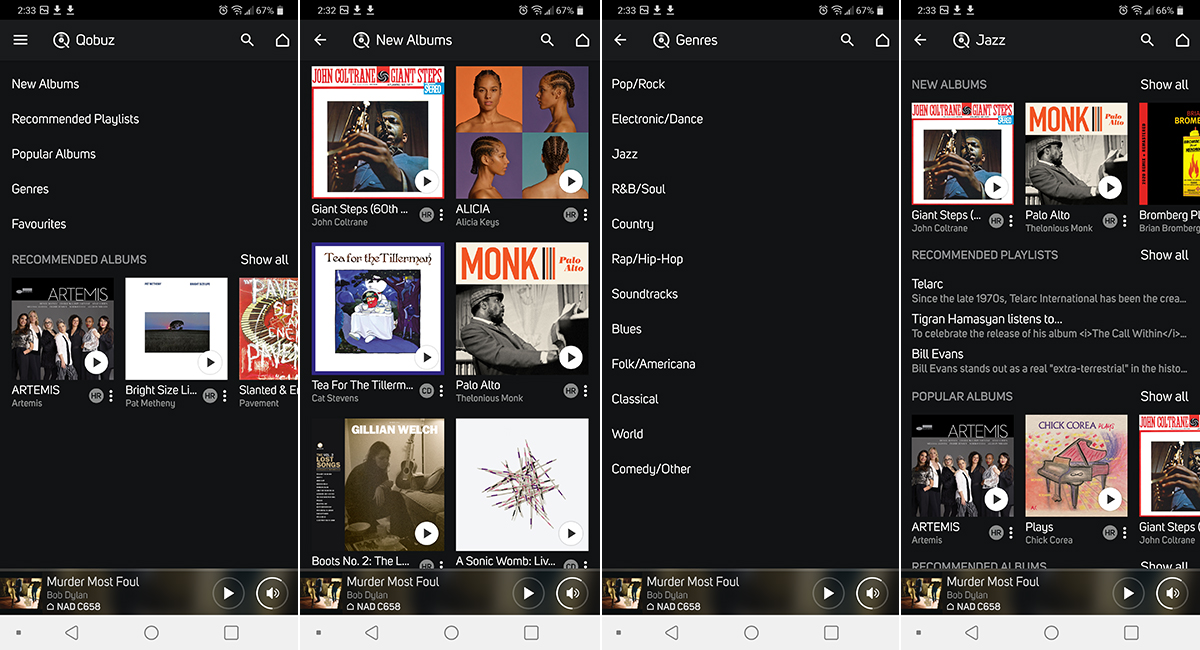

I’ve used all of the services cited above, but I’m most familiar with Qobuz. There are lots of things I like about the service, notably its large selection of hi-rez music in my preferred genres: jazz, classical, roots/folk, world, and prog rock. The mobile and desktop apps have some features I use heavily -- viewing album booklets (when these are made available by the label), Press Awards, excellent editorial content, playlists and other discovery tools, and the ability to filter music by multiple genres. To my knowledge, the album-booklet feature is unique.

When choosing a streaming service, there are factors other than music selection and the availability of lossless and hi-rez content. You want to know how you’ll interact with the service, which means checking out its mobile and/or desktop apps. Different listeners have different priorities, which will influence their choice. For example, Idagio and Primephonic customize their metadata for classical listeners, whose needs are very different from fans of more mainstream genres.

I think it’s safe to say that most streaming subscribers either listen through headphones, or stream from a mobile device to a Bluetooth speaker. But audiophiles are adding streaming components to their music systems, and using them for serious sit-down listening.

Use what you know

If you want to keep using the mobile app for your streaming service when playing through a streaming component, you can almost certainly do so. Bluetooth has become a nearly ubiquitous feature of the products we review on Simplifi: powered and active speakers, streaming DACs, streaming amplifiers, etc. So if you want to play music from a streaming app on your phone through your sound system, pair the phone with the streaming component, hit play, and listen.

But sound quality may take a hit. Although the most recent Bluetooth standards have enough bandwidth to transmit two-channel audio of lossless CD resolution, almost all Bluetooth codecs employ lossy compression.

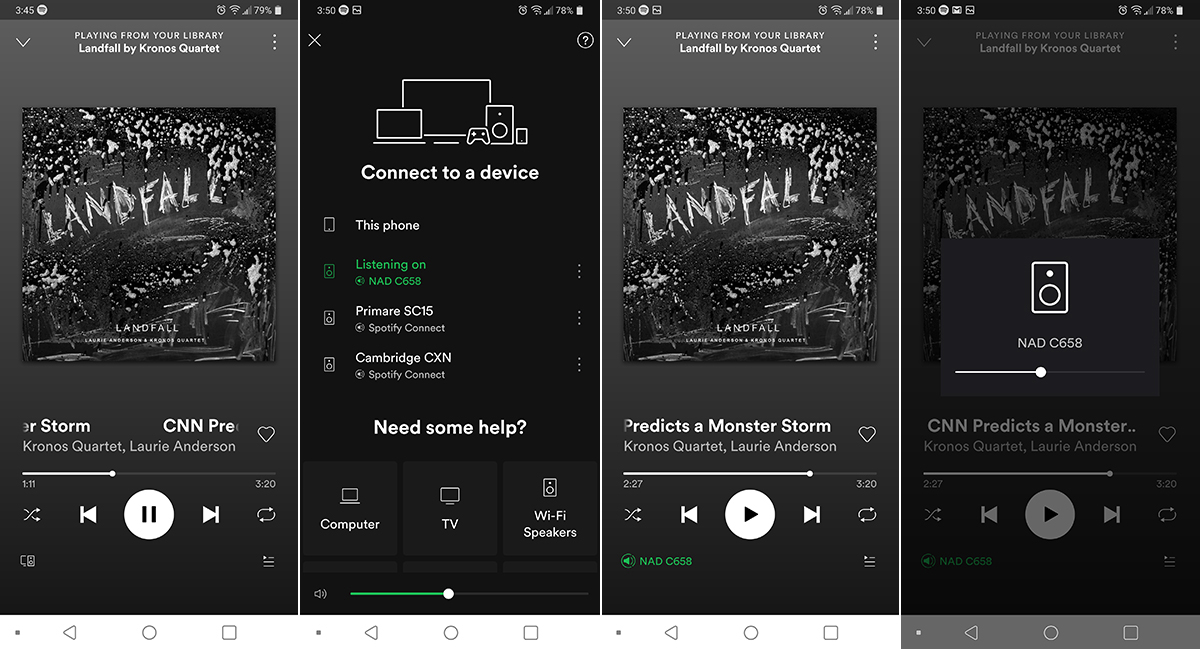

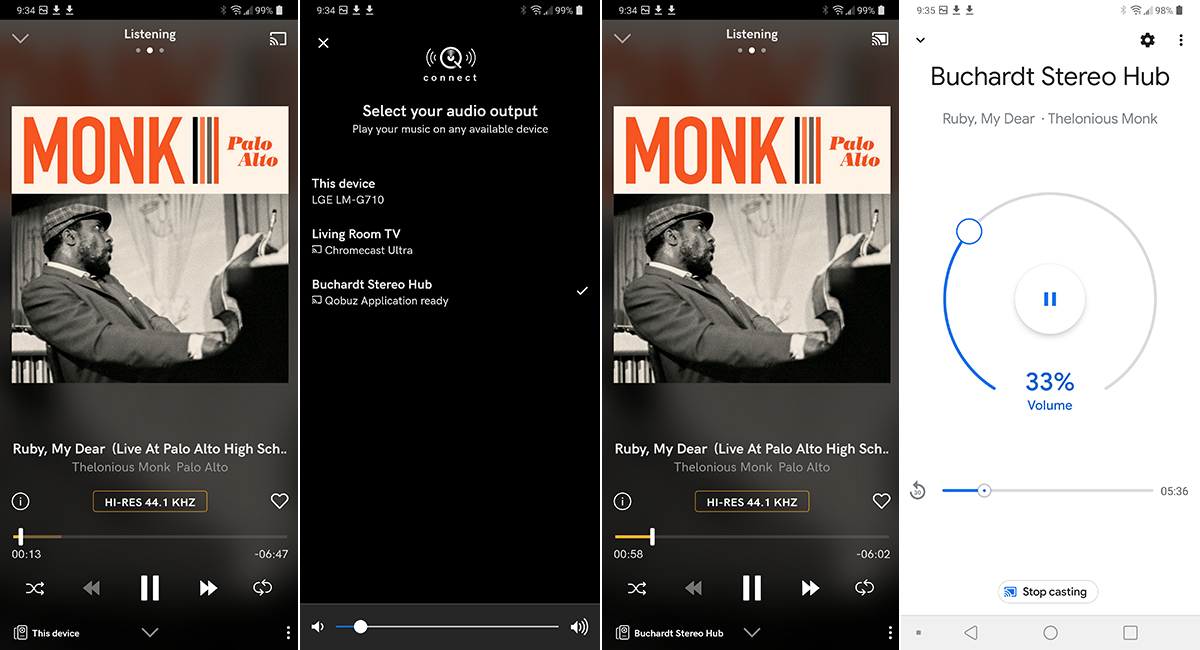

You may also be able to stream audio from your mobile app over Wi-Fi. If your streaming component supports Spotify Connect, you can play directly from the Spotify app, and adjust your component’s volume control using the app. Spotify uses lossy compression, but with Wi-Fi, the stream won’t be uncompressed and recompressed, as it will with Bluetooth. Tap the Devices Available icon at the bottom of the Spotify screen, choose the Spotify Connect component you want to use, and playback will shift to that component.

If your component supports Apple AirPlay, you can send to it CD-resolution (16-bit/44.1kHz) lossless audio from any music app on your iPhone or iPad. If you have multiple components that support AirPlay 2, you can send lossless 16/44.1 audio to any or all of them, with independent control over volume for each zone. AirPlay and AirPlay 2 resample all audio to 16/44.1 -- they don’t support hi-rez audio.

If your component has Chromecast Built-in, you can stream hi-rez audio at up to 24/96 resolution from any Cast-enabled app on your mobile device. Use the Google Home app to add the Chromecast component to your network, then tap the Cast icon in your music app to shift playback from your device to the Chromecast component.

As I discussed in “Rules of the Game,” my March 1 feature on streaming protocols, Chromecast and Spotify Connect have two advantages over Bluetooth and AirPlay. Your mobile device serves only as a controller, for choosing music, selecting the playback component, and adjusting volume. Music streams directly from your network router to your component without going through your phone, so there’s much less of a drain on the phone’s battery.

Chromecast’s downside is that it doesn’t support gapless playback, instead adding a delay of a second or two after each track. For many listeners, this won’t be a big deal, but it will matter a lot for some albums and genres.

Purpose-built

While many networked components rely on protocols like AirPlay, Chromecast, Spotify Connect, and UPnP/DLNA to enable streaming, a large number have their own apps, or serve up a Web interface for controlling the component. I’ve reviewed many of these products on Simplifi, from brands such as Bluesound, Bryston, DALI, iFi, KEF, Lumin, NAD, Naim, Pro-Ject, SVS, Volumio, and Yamaha. The apps for all of these brands incorporate client software for many streaming services.

As I own an NAD Classic C 658 streaming DAC-preamp ($1649), I’m very familiar with the BluOS app that controls its streaming features. And, as noted, I use Qobuz heavily. (I’ve also streamed from Amazon Music HD, Idagio, and Tidal using the BluOS app.) When streaming from Qobuz in the BluOS app, I don’t have access to album booklets, as I do with Qobuz’s own apps or with Roon. I don’t mean to single out NAD and Bluesound here -- support for Qobuz album booklets isn’t available in the apps for any of the streaming components I’ve reviewed for Simplifi. (Naim and Volumio both say that this feature is on their development lists.)

However, BluOS lets you filter releases by genre, something you can’t do with the Qobuz clients in some other products I’ve reviewed, such as Volumio’s Primo streaming DAC and Pro-Ject’s Stream Box S2 Ultra music streamer (which uses a reskinned version of Volumio’s software). But whereas Qobuz’s desktop and mobile apps let you specify multiple genres, with the Qobuz client in BluOS you can filter by only one genre at a time.

The Primo, and Lumin’s T2 network streamer, support another Qobuz feature I enjoy: Press Awards. I’ve found a lot of great music with this tool, which is not available in BluOS’s Qobuz client. As part of its optional MyVolumio Superstar plan (€66.99/year), Volumio offers editorial content for both streamed and locally stored music. When streaming from Qobuz and Tidal in the Naim app, you can view editorial content such as artist bios and album information, just as you can do in those services’ desktop and mobile apps.

There are also variations in file-format support. The Qobuz client in the Müzo app used for iFi’s Audio’s streaming components doesn’t support hi-rez playback, even though the hardware does. Hi-rez content is played at 16/44.1 resolution. This is unusual -- the Qobuz clients in the apps for most other streaming products do support hi-rez audio. Tidal users who want to play MQA-encoded Masters content may want to make sure that their component and its companion app support MQA.

I could go on and on, but you get the picture. While many component manufacturers let you use their proprietary apps to stream from online services, these apps don’t offer all the features of those services’ desktop and mobile apps, and they vary in the features they do support.

Local content

If manufacturers’ apps aren’t as rich as those provided by the streaming services, why use them at all? Why not use a protocol like AirPlay, Chromecast, or Spotify Connect to stream to your component of choice? If all you’re doing is streaming from the Internet, that might be a viable option.

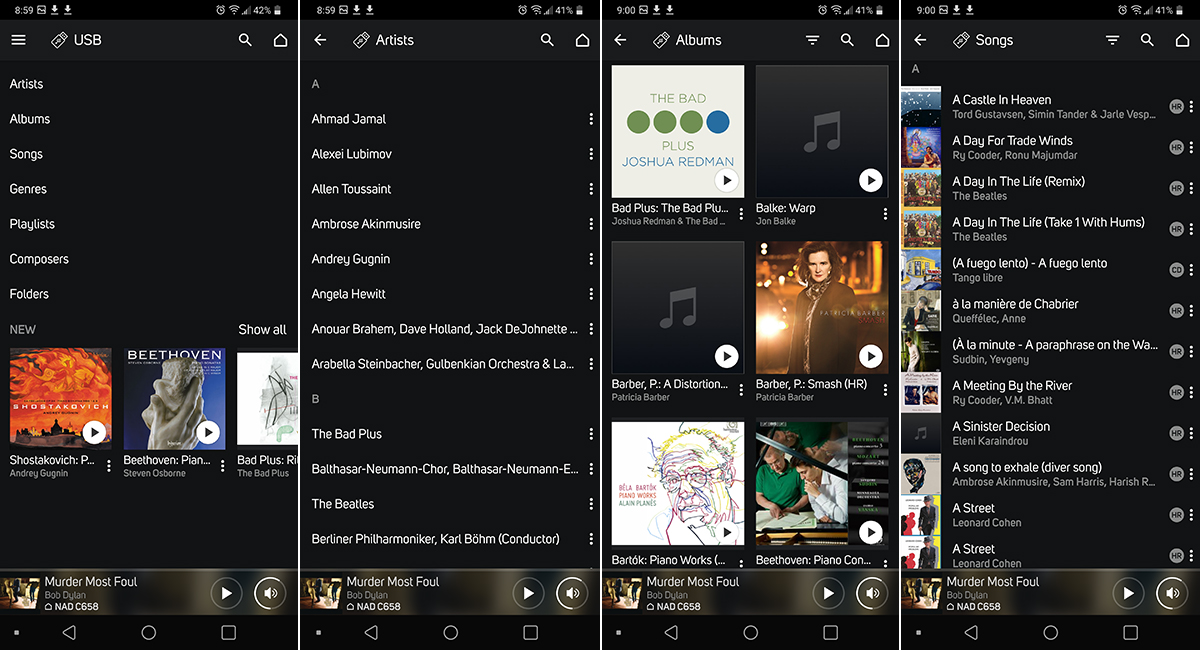

But even though streaming is becoming the way most people get new music, many listeners have large libraries of downloaded and ripped music files. To play these through a streaming component, they’re almost certainly going to need to use the app for that component. If that’s the case, it probably makes sense to use the same app for streamed and locally stored music.

Many streaming components have USB Type-A ports that let you attach an external drive loaded up with digital music. Many also let you play music stored on network drives. However, there are variations in the way audio components’ apps handle locally stored music.

Here’s a particularly bad example. For playing locally stored music, iFi Audio’s Pro iDSD streaming DAC-preamp and the Aurora wireless music system both have a USB Type-A port for connecting an external drive and a microSD card slot. But when I reviewed these products, the app listed the contents of a connected drive or inserted card as a long, alphabetical list of files. Not only was there no metadata, the app didn’t even organize files into folders -- it was virtually impossible to find the music I wanted to hear. If iFi hasn’t yet issued a software update to fix this issue, I hope it soon will.

All other streaming components I’ve used do a pretty good job of organizing locally stored music. Not perfect, though: few apps display all of the album art embedded in music files. While most apps will let you sort locally stored music by artist name, album title, track title, and genre, not all do. For example, the current version of Volumio sorts alphabetically by artist name, but not by album title. You can view albums, but they’re presented in apparently haphazard order. On the other hand, Volumio lets you edit metadata for local content from within the app -- an unusual capability.

There’s another reason to use the manufacturer’s app: You probably need it for setup, and you may need it to adjust audio settings such as room-boundary compensation, room correction, subwoofer crossover frequency, and dynamic equalization. Also, many streaming components can be grouped together for multi-zone playback -- and in many cases, this requires the use of a proprietary app.

Takeaways

If software has become a critical part of the listening experience, that means it deserves careful attention by anyone who’s shopping for a streaming component. Here’s some advice:

If you haven’t already settled on a streaming service, try a few different ones to find which one has the combination of music selection, editorial content, discovery tools, and software polish that best suits you. All services offer free trial periods for this purpose. And if you become disenchanted with a service and want to check out alternatives, there’s no big financial hit.

But if you’re buying a streaming component, mistakes can be expensive. If possible, get a demo of the component’s software. Assess its responsiveness, visual polish, ease of use, and design consistency. Does it apply the same conventions for different functions? Is it clear how different functions work? When you’re scrolling through music listings, are results updated quickly, or is the app sluggish?

Do some homework. After choosing a streaming service, dive deep into the service’s mobile and/or desktop apps, and make a note of the features you most use. For example, if the ability to filter new releases by genre is important to you, make sure that feature is available in the component’s app. If the app doesn’t support features that are important to you, check to see if it’s possible to stream to the component from the service’s app via AirPlay or Chromecast.

If you plan to use the component to play your own music files, load a FAT32-formatted thumb drive with a few dozen albums, then see how the app presents this content, and how you navigate through it. Does the app organize your music in a way that makes sense to you and that matches your listening habits?

With the move to streaming and the disembodiment of music, software has become the way most of us interact with our music systems. It’s important to get it right.

. . . Gordon Brockhouse