Was 2021 the year that lossless and hi-rez music streaming became mainstream? Last year, Spotify promised it would start delivering lossless music, but failed to deliver. Three months later, Apple announced plans to offer lossless and hi-rez content, and started delivering shortly thereafter. Amazon Music HD had been offering lossless and hi-rez music since 2019; but following Apple’s move, Amazon reduced its price for the service. These aggressive moves by major providers like Apple and Amazon led several smaller streaming services to revamp their own pricing plans in 2021.

Still waiting

With 356 million active users—including 165 million paid subscribers—Spotify is the world’s largest on-demand music streaming service by a healthy margin. Currently, Spotify uses Ogg Vorbis lossy compression, with a maximum bitrate of 320kbps, to deliver music. But a year ago this month, Spotify announced plans for a lossless tier. “For those listeners really passionate about audio quality, later this year, we’ll be launching a new subscription offering—Spotify HiFi,” said Jeremy Erlich, Spotify’s global co-head of music.

The announcement was spotty on details. Spotify HiFi “will begin rolling out in select markets later this year,” the company stated in a backgrounder. The service would be available on the Spotify app installed on such devices as smartphones, tablets, PCs, and Macs, and on components that support Spotify Connect. But there was no information about timeline, launch markets, or pricing. And there were other questions: Would all tracks on Spotify be available at lossless CD resolution (16-bit/44.1kHz) to HiFi subscribers, or would some tracks only be available in a lossy format? Would Spotify offer any music at higher resolutions?

No matter—2021 has come and gone (good riddance!), and there’s still no sign of Spotify HiFi. That doesn’t necessarily mean it was vaporware. In the spring, some users reported seeing a Spotify HiFi button in the Spotify app. During the year, I spoke with a few audio manufacturers whose products support Spotify Connect, and they told me these products would play lossless audio from Spotify HiFi, whenever the service launched. No surprise there; Spotify had said the best way to experience Spotify HiFi would be to use Spotify Connect.

So when can we expect Spotify HiFi? That’s anyone’s guess. “We know that HiFi quality audio is important to you,” reads a company post on Spotify Community. “We feel the same, and we’re excited to deliver a Spotify HiFi experience to Premium users in the future. But we don’t have timing details to share yet.”

Why the delay? Some people speculate that Spotify was blindsided by Apple’s launch of lossless and hi-rez audio, and specifically by Apple’s aggressive pricing.

Competition

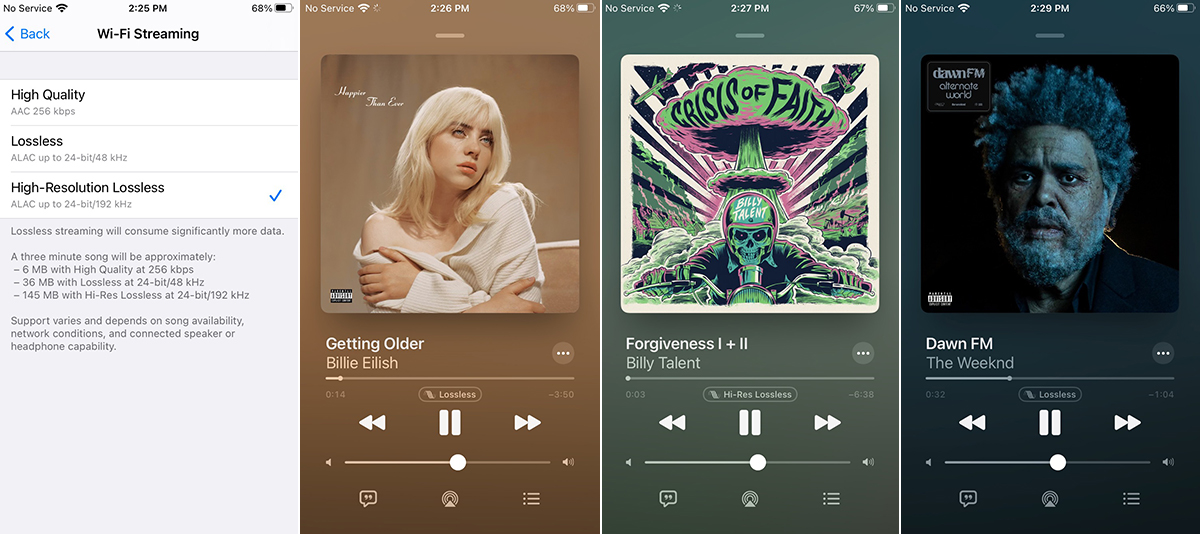

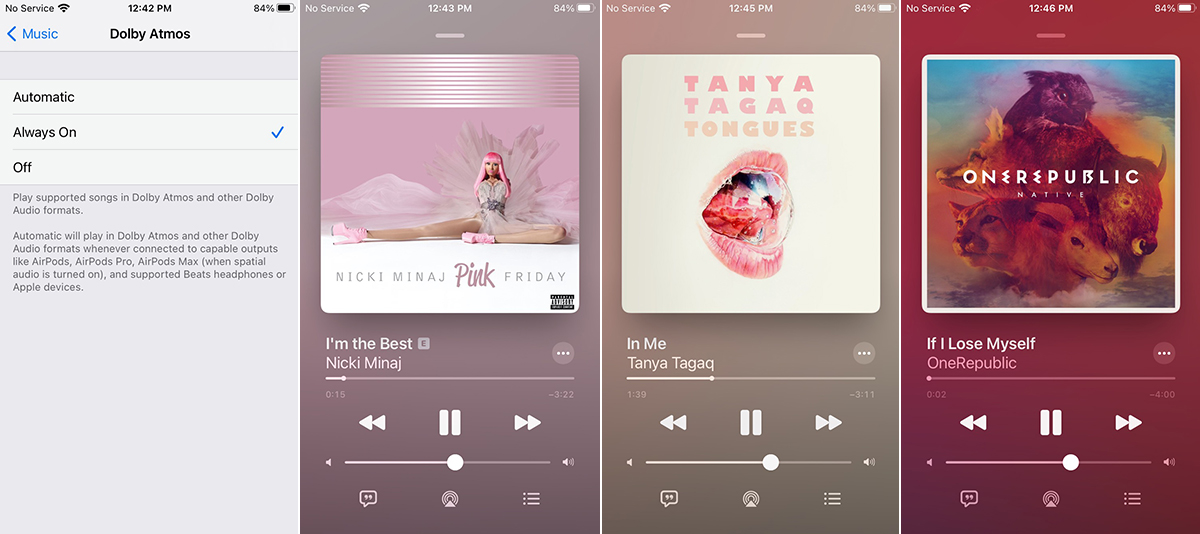

Apple Music has an estimated 98 million active users, all of whom are paid subscribers—unlike Spotify, Apple does not offer a free tier. Until mid-2021, Apple Music was streaming in the lossy AAC format, at 256kbps. On May 17, Apple Music announced it would make all tracks available in Apple Lossless (ALAC) format, at either 16/44.1 or 24/48 resolution; and a substantial number of albums would be available at higher resolutions, up to 24/192. Apple also announced plans to offer Dolby Atmos–encoded spatial audio versions of some albums.

Those enhancements went live on June 7, the first day of Apple’s Worldwide Developers Conference. Subscribers can still stream in AAC format—the lower data rate is obviously advantageous for streaming over cellular networks.

Apple is not charging extra for lossless, hi-rez, or spatial audio—these enhancements are included in the standard subscription fee of $9.99 per month (all prices in USD). Did Apple’s pricing make it less attractive for Spotify to launch its HiFi tier? If Apple wasn’t charging more for lossless audio, how could its competitors?

That was certainly Amazon’s take. Until Apple’s move, Amazon had been charging $14.99/month ($12.99 for Prime members) for Amazon Music HD, compared to $9.99/month ($7.99 for Prime members) for Amazon Music Unlimited, which uses lossy compression. Now Amazon Music HD is available to Amazon Music Unlimited’s 75 million subscribers at no extra cost.

Qobuz and Tidal also responded. In September, Qobuz, which has about 200,000 subscribers worldwide, dropped the monthly fee for its Studio Premier tier from $14.99 to $12.99. All of Qobuz’s content is available in lossless CD resolution, and some is in hi-rez, up to 24/192.

Tidal—with a claimed 3 million subscribers—had been charging $9.99/month for its Premium tier, which used lossy compression with a maximum bitrate of 320kbps. Its HiFi tier offered lossless CD-resolution audio in FLAC format, hi-rez audio in MQA format, and spatial audio in Dolby Atmos and Sony 360 formats, for $19.99/month. In November, Tidal announced a free, ad-supported tier. The free service is available only in the US, and sound quality is compromised because it uses lossy compression at a maximum bitrate of 160kbps. Tidal also split its HiFi tier in two. For $9.99/month, Tidal HiFi offers lossless CD-resolution music. For $19.99, Tidal HiFi Plus gives subscribers access to MQA-encoded hi-rez content, as well as spatial audio tracks. Subscribers to these tiers can cue up music in the Tidal app on a smart device, and then transfer playback to a component that supports Tidal Connect. This feature is not available for the free tier.

Jumping through hoops

As I outlined in my feature on Apple Music last year, Apple doesn’t make it easy to stream hi-rez music, especially if you want to listen through speakers rather than headphones. The best way to play lossless and hi-rez music from Apple Music through a component audio system is to connect an iPhone or iPad to a DAC via USB. To do that, you’ll need a Lightning-to-USB adapter.

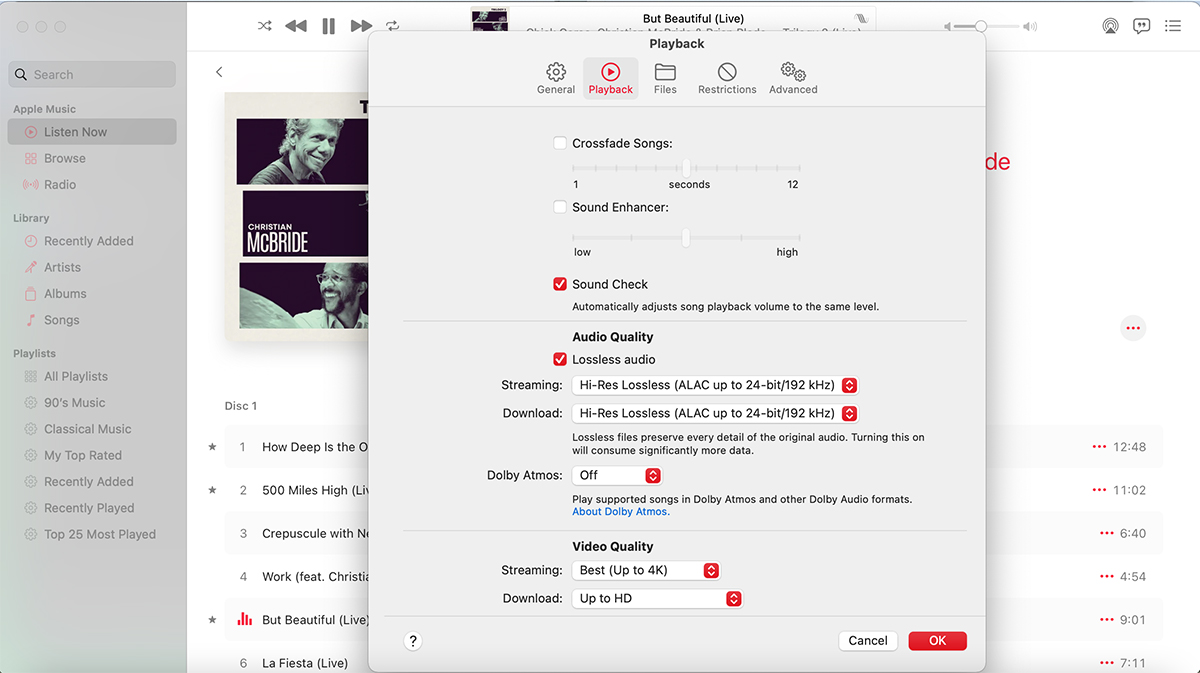

You can also access Apple Music on a computer connected to a USB DAC, but that’s not ideal. A Mac will not automatically output lossless audio to a connected DAC at the native resolution of the stream. Instead, it will convert output to whatever resolution has been set in macOS’s Audio MIDI Setup utility.

What if you want to stream hi-rez audio wirelessly from Apple Music to your sound system? That’s not possible. Most streaming components have integrated support for streaming services like Tidal, Qobuz, Deezer, and Idagio, all of which offer lossless audio. But as far as I’m aware, the only brand with integrated support for Apple Music is Sonos. With other brands, you have to use AirPlay if you want to stream audio from Apple Music over your home network to your music system.

As I said in my July 1 feature on Apple Music, that involves some compromises. “Even if you’re streaming high-resolution music to your i-device, and the AirPlay component you want to use supports hi-rez, what you’ll get is CD resolution,” I wrote. “With audio, AirPlay streams everything in 16/44.1 ALAC format, regardless of the resolution of the source file.” In fact, the compromises are even greater.

Apple requires that AirPlay 2–compatible components be capable of receiving and processing 16/44.1 ALAC streams. But that doesn’t mean your device will be sending a lossless stream. I now understand that Apple devices use AAC compression, at 256kbps, to send music to AirPlay 2 components when using the Core Audio engine in iOS or macOS. Let’s say you’ve enabled hi-rez streaming on your i-device, and you’re playing an album that’s available in 24/192. Your device will output 24/192 to a connected USB DAC (assuming the DAC supports that resolution). But if you stream the same album wirelessly, your device will send a compressed 256kbps AAC stream.

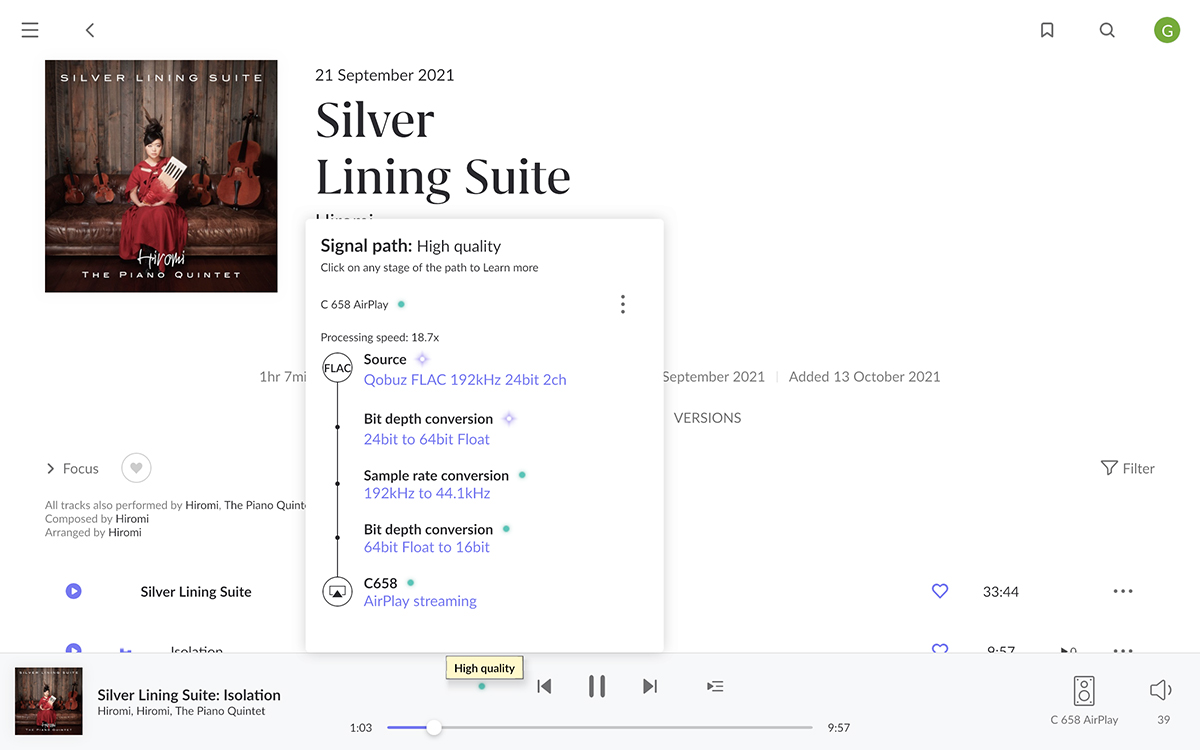

What difference does that make? To find out, I enabled lossless streaming on my iPhone 8 and cued up the first track of Hiromi Uehara’s Silver Lining Suite (24/192 ALAC, Concord Jazz/Apple Music), performed by the Japanese jazz pianist’s quintet, featuring violinists Tatsuo Nishie and Sohei Birmann, violist Meguna Naka, and cellist Wataru Mukai. I streamed “Isolation” from my iPhone via AirPlay to my NAD C 658 streaming DAC ($1749), and then streamed the same song from Roon (24/192 FLAC, Concord Jazz/Qobuz) to the C 658 via AirPlay. For AirPlay streaming, Roon resampled the song to 16/44.1 ALAC, bypassing Core Audio on the Apple Mac Mini that I use to run Roon Core 1.8. If my iPhone had been streaming the song in 16/44.1 ALAC, the two streams would have sounded identical.

They did not. With the CD-resolution ALAC stream sent by Roon, the soundstage was deeper than when I streamed the same track from my iPhone. There was more air around the instruments, and the tone of the strings was a tad smoother. Microdynamics were slightly better, so that I could better appreciate Hiromi’s touch and phrasing, but the differences were nowhere near night-and-day. I could happily have listened to the whole album streamed to the C 658 from my iPhone.

The enemy of the good

So how much does this lossless and hi-rez stuff matter? Less than many audiophiles think. In his February 2022 editorial on SoundStage! Access, “The Most Dangerous Myth in Audio,” Dennis Burger castigated “golden-ear” audiophiles who vastly overstate miniscule sonic differences (or posit to hear differences no one else can hear), and then recounted a couple of instances where that mindset alienated people who might otherwise enjoy hi-fi:

Some years back, I made the acquaintance of a friend of my daughter who expressed some interest in what I do for a living. “I’ve always thought it would be nice to have a good stereo system like the one my dad had,” he told me. “But I don’t know.”

I could feel that “I don’t know” doing a lot of heavy lifting, so I pressed him. What was his barrier to entry? Was it money? Space? Time? Analysis paralysis? He finally confessed: “Well, I’ve listened to a lot of music on iTunes and a lot of music on CDs, and I honestly can’t tell much if any difference, so I feel like real speakers and real amps and stuff would just be wasted on me.”

When I told him that no one could hear much if any meaningful difference between a really well-encoded 256 VBR AAC file and a Red Book version of the same master, it was almost as if I’d committed heresy. But it also gave him permission to maybe dip his toes into this whole hi-fi thing.

Another young acquaintance sometime later had been exposed to the same overblown rhetoric, but instead of responding with feelings of inadequacy, he woke up and chose violence, writing off our entire hobby as one big scam. “You old guys tell me that Spotify sounds like garbage at the same time you’re trying to sell me an amp that costs more than I pay in rent for a year. But let’s assume for the sake of argument that you’re right; why would I spend so much money on this stuff if the supposed improvements in sound quality are only perceivable by a handful of crazy, old, half-deaf dudes?”

Amen to that—Spotify’s compressed Ogg Vorbis streams do not sound “like garbage”; nor do Apple Music’s AAC streams. It’s dishonest and curmudgeonly to suggest that anyone who enjoys these services has poor hearing or poor taste. In Mes Pensées, the 18th-century French philosopher Montesquieu observed that the better is the enemy of the good. But better sound is available, as I confirmed by the two following experiments.

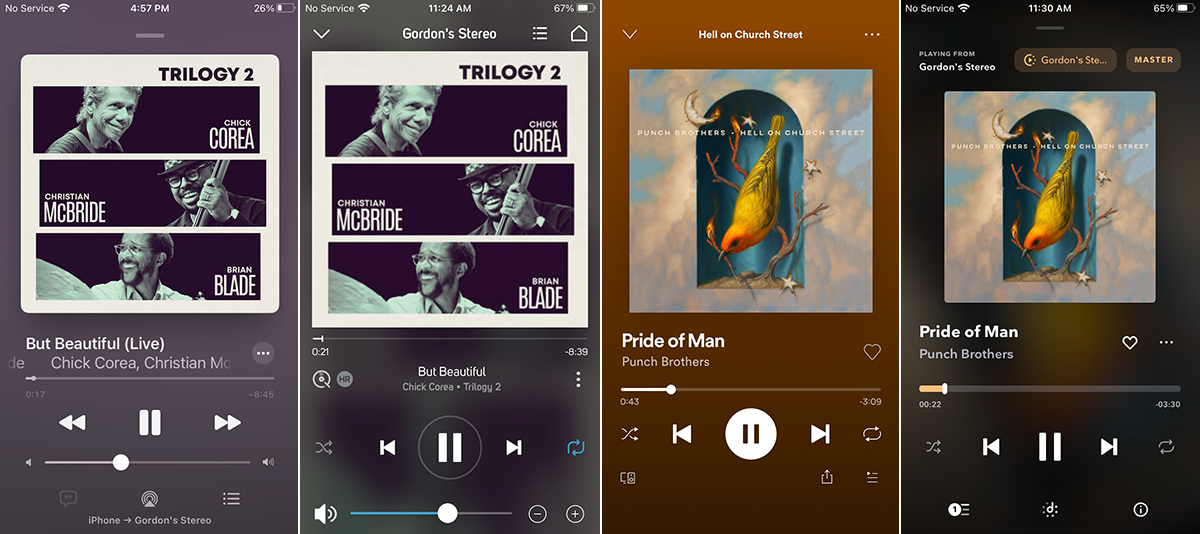

For the first, I turned off lossless audio on my iPhone 8, so that it would stream in 256kbps AAC from Apple Music, and then cued up “But Beautiful,” from Trilogy 2 (Concord Jazz/Apple Music), a live concert compilation by the Chick Corea Trio, and streamed the song via AirPlay to my NAD C 658. In the BluOS app that controls the C 658, I streamed the same song from Qobuz in 24/192 FLAC format. The Qobuz hi-rez stream sounded fuller and more transparent, and the soundstage was deeper; the Apple AAC stream was a little more closed-in. I don’t want to overstate the difference—the compressed Apple stream was certainly enjoyable, but the hi-rez Qobuz stream was better. I think almost anyone would hear the difference.

For my second experiment, I turned to Punch Brothers’ new album, Hell on Church Street (Nonesuch Records). I streamed “Pride of Man” to the C 658 via Tidal Connect and Spotify Connect. With Tidal, I was hearing a 24/96 MQA stream, which the C 658 decoded and rendered; with Spotify, I was hearing a 320kbps Ogg Vorbis stream. Again, I heard differences between the two streams; and again those differences were nowhere near night-and-day—but I think almost anyone would hear them. With the Tidal stream, the sound was a little warmer and more inviting. There was more space and air around the musicians. With the compressed Spotify stream, the sound was more closed-in, a little more opaque; the bluegrass instruments sounded a little harsher, and there was a bit of a buzzy edge around Chris Thile’s voice.

These experiments confirmed my belief that hi-rez streaming makes a difference. If you can get it at no extra cost, or for a few dollars extra, I think it’s a no-brainer.

Spaced out

Hi-rez audio wasn’t the only development in music streaming in 2021, or even the most important. Apple’s embrace of spatial audio was big news. Tidal and Amazon already offered Dolby Atmos music, but Apple’s move into this space could help drive spatial audio into the mainstream.

I’m a two-channel guy—there’s not enough room in our small Toronto rowhouse for a surround system. But Vince Hanada, a longtime SoundStage! Network reviewer who lives on Canada’s west coast, has a full-blown 7.4.1 Dolby Atmos setup, and in a November 2021 feature on Simplifi, Vince wrote about playing surround music from Apple and Tidal through that system. “It’s great to see new artists and producers taking up this medium not only to enhance stereo reproduction,” he concluded, “but also to come up with new and creative uses for the extra speakers available in the formats. I like the clout of Apple Music behind it as well—it has a real chance of staying relevant.”

Even though Apple’s and Tidal’s Atmos streams use Dolby Digital Plus compression, Vince liked what he heard. “I wasn’t too concerned by the low-resolution sound I heard at times,” he wrote. “The enhanced imaging and the ‘bubble of sound’ that the format creates have their own intriguing qualities.”

But I’ve heard contrary opinions. A few weeks ago, Roger Kanno, another west-coast SoundStager, sent me an email about his take on surround streaming. “One thing I noticed is that the compressed bitstream from Tidal (I am assuming that it is Dolby Digital Plus) doesn’t sound that great. For example, The Weeknd’s new album has a great mix, but the fidelity seems a bit lacking compared to the hi-rez stereo version. And Kraftwerk 3D and R.E.M.’s Automatic for the People, which I have in uncompressed TrueHD, are not as good on Tidal.” Spatial audio is a whole new frontier, and we’ll have more to say about it on Simplifi in 2022.

There was one other development in 2021 that’s near and dear to my heart. On August 30, Apple announced that it had purchased Amsterdam-based Primephonic, a streaming service that specializes in classical music. As I wrote in a September 2019 feature, “Streaming the Classics,” classical listeners need richer and more consistent metadata than they get from the major streaming services. Primephonic has created a database of the major works of over 2000 composers, and it uses this catalog as the basis of its metadata rather than what the record labels supply. Apple says it plans to launch a dedicated classical app that will make it easier for classical listeners to find the music they want to hear on Apple Music. This is something I’ll be watching closely in 2022.

. . . Gordon Brockhouse