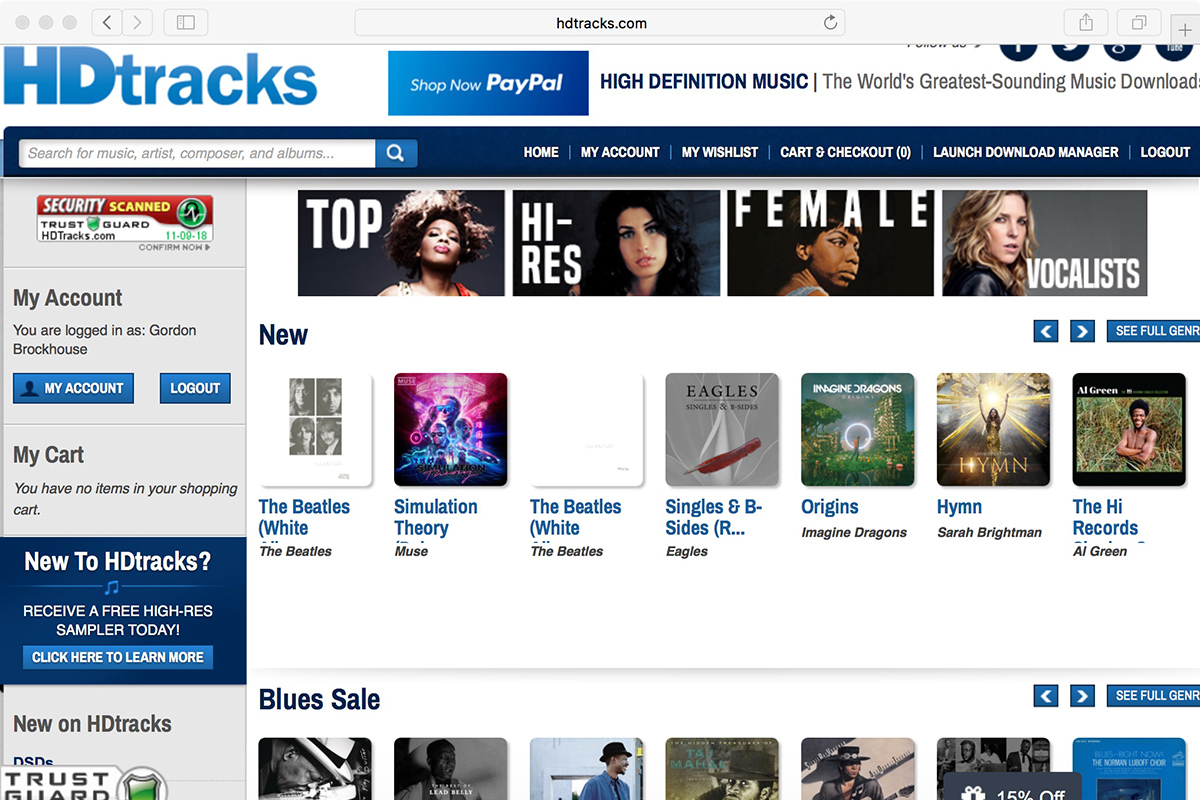

This fall marked the 10th anniversary of file-based, high-resolution audio playback. The New York City-based website HDtracks opened its virtual doors in March 2008; in October of that year, it added to its catalog 24-bit/88.2kHz and 24/96 FLAC files.

At that time, hi-rez digital music was available on physical media, notably SACD, which was introduced in 1999. In the recording studio, hi-rez audio dates back to the mid-1990s. But until David and Norman Chesky launched HDtracks, audiophiles had been unable to purchase DRM-free hi-rez music.

The Chesky brothers have deep roots in music: David as an active composer and performer, Norman as a respected producer. Together, they own an audiophile record label, Chesky Records, which they formed in 1986. David Chesky says the idea of opening an online music store came to him while he and Norman were walking down Broadway Avenue. “I said to my brother, ‘You see all these stores? One day they won’t be here.’ About a year later, we launched HDtracks. People thought we were nuts.”

David Chesky

David Chesky

HDtracks’ first hi-rez content came from audiophile labels: Chesky Records, of course, but also 2L and Reference Recordings. Support from major labels and artists grew steadily over the next few years. Within five years, HDtracks was offering hi-rez versions of music by Bob Dylan, Michael Jackson, Paul McCartney, and the Rolling Stones, as well as by acclaimed jazz and classical musicians.

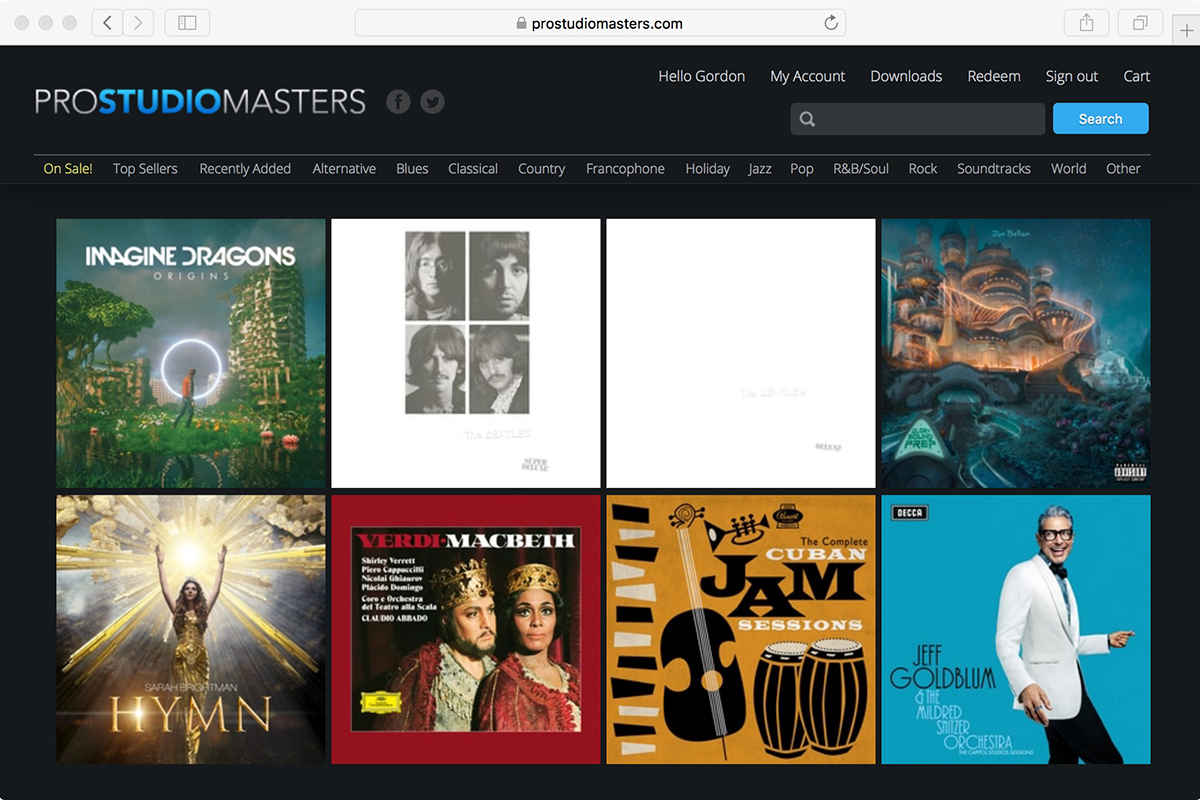

Today, several other sites offer hi-rez music, many specializing in classical music. These include Sweden’s eClassical.com, as well as sites operated by British labels such as Chandos, Hyperion, and Linn. Paris-based Qobuz and Montreal-based ProStudioMasters (which celebrated its fifth anniversary in September) offer hi-rez downloads spanning all genres.

End of an era?

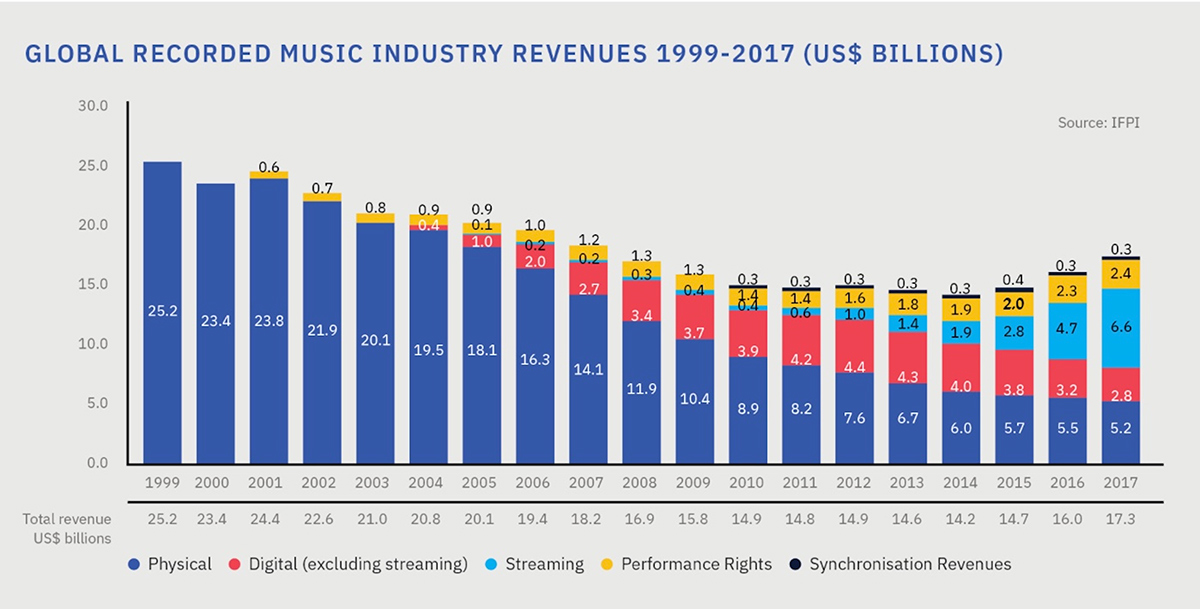

Ten years after the launch of HDtracks, the download model is waning. According to the Global Music Report 2018 of the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI), streaming is now the largest contributor to global music-industry revenues. In 2017, streaming revenues totaled $6.6 billion (all figures USD) -- 40% higher than the previous year. Revenues from downloads were $2.8 billion, down 12.5% from 2016, and down 43% from their peak of $4.4 billion in 2014. Surely, we can expect these trends to have accelerated in 2018 and beyond.

Oles Protsidym, CEO and founder of ProStudioMasters, says that declines in downloads are being felt mainly by mainstream websites such as Apple’s iTunes store (which uses lossy AAC compression) and Amazon Music (which uses MP3). “We don’t see any decline,” he says. “Many of our customers use streaming services as a discovery tool, then come to us to buy music by artists they find through streaming.”

Protsidym acknowledges that hi-rez download sites are a small niche market, but that they have “the potential to be much larger.” They’ve been able to prosper within their niche because they offer a sonic advantage that the large streaming services don’t.

That advantage is disappearing. Tidal already offers over 58 million tracks in lossless CD resolution, and now has a million or so in hi-rez. Qobuz is preparing to expand beyond its base in Western Europe, though it now looks as if its American launch won’t happen until 2019. It has 40 million lossless CD-rez tracks, and a claimed 2 million in hi-rez.

Qobuz has yet to set a date for its US launch, but has announced pricing plans. Qobuz Premium (MP3 at 320kbps) will cost $9.99 per month or $99.99 annually. Qobuz Hi-Fi (lossless CD resolution) will cost $19.99 per month or $199.99 annually. Qobuz Studio, which adds access to hi-rez content to 24-bit/192kHz, will cost $24.99 per month or $249.99 annually. The top tier is Sublime+, which costs $299.99 annually. In addition to high-rez streaming, it also includes significant discounts on downloads from Qobuz.

Dan Mackta, managing director of Qobuz USA, confirms that Qobuz’s download sales are falling in Europe, but says these declines are offset by its growing streaming revenues. “Declines in downloads are happening across the board, including the hi-rez world,” he adds. “The lossy download world is basically toast.”

Dan Mackta

Dan Mackta

David Chesky says that HDtracks “saw no effect” after Tidal launched its hi-rez Masters tier in early 2017. But he knows that, at some point, hi-rez streaming will take a bite out of hi-rez downloads. “I know it’s coming,” Chesky says, “but we haven’t experienced it yet.”

The future

For the last couple of years, there have been repeated reports that HDtracks is planning a streaming service. That speculation is accurate, Chesky says. “We have all the capabilities in place. We just have to throw the switch.”

Still, he’s not itching to make the move. “No streaming company is making any money,” Chesky explains. “Musicians aren’t making money from streaming. So what is the point?” Whenever HDtracks does throw the switch, “it’s got to be good for customers, and it’s got to be good for musicians. This is what I do, and I want to do it well.”

Chesky believes there’s a future for downloads. “Playing a download sounds better than listening to a stream,” he maintains. “And people want to own and collect.”

Qobuz’s Dan Mackta has a slightly different perspective. Hi-rez downloads have “a dedicated user base,” he observes, who are motivated by an “urge to collect, and a perceived advantage in sound quality. But they’re an older audience. At some point in the future, they’re going to represent a very small niche. New audiophiles are not in a rush to get into a collecting mindset.”

In demographic terms, boomers like to collect, millennials prefer to stream. That’s the basis of one of Chesky’s biggest worries about the future of high-performance audio. “My big concern is getting young people into this hobby,” he says. “What’s keeping them away?”

What about the sound?

Tidal and Qobuz have changed the way I consume music. I came late to streaming, because I didn’t think services that use lossy compression could deliver the sound quality I want for serious sit-down listening. Tidal and Qobuz do.

While some observers (including Chesky) posit a difference in sound quality between streamed and locally stored music, this is something I’ve never noticed. To confirm my general impression, I did some comparative listening between high-rez streams from Qobuz and high-rez downloads in my music library.

Through my headphone rig, HiFiMan Edition X V2 planar-magnetic headphones and an iFi iDSD Micro Black Label DAC-headphone amp, a 24-bit/96kHz FLAC download and 24/96 FLAC stream of Keith Jarrett’s iconic Köln Concert (ECM ) from Qobuz sounded exactly the same, that is to say, wonderful. Comparing a 24/96 download and streams of Poulenc’s Piano Concerto played by Louie Lortie and the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Edward Gardner (Chandos), my experience was exactly the same. Everything was played through a Mac Mini running Audirvana 3.1.12.

In my living room, I cued up a 24/96 FLAC download from ProStudioMasters and 24/96 FLAC stream from Qobuz of a 2015 live performance of Shostakovich’s Symphony No.10 by the Boston Symphony Orchestra led by Andris Nelsons (Deutsche Grammophon), playing them through the magnificent Kii Three DSP-controlled active speaker system (review pending). To my surprise, the download sounded slightly more dynamic, and slightly less harsh. String tone seemed breathier on the download, and a bit more wiry on the stream. Whatever the differences, they were very slight to the point of insignificance.

I heard no difference at all between a 24/88.2 FLAC download and a 24/88.2 FLAC stream of a delicious cover of Nat King Cole’s “Calypso Blues” by the Korean singer Youn Sun Nah, both from her 2009 album Voyage (ACT Music). Everything was played from a Bluesound Vault 2i (review pending), connected via S/PDIF to the Kii Control using a 5m AudioQuest Carbon digital coax cable.

A new mindset

All of this raises the question, when you can pay a flat monthly fee to stream millions of albums in lossless quality, and hundreds of thousands in high-rez, what is the point of paying for a download? I’m certainly buying way less music than I used to. Instead of downloading 50 or 60 new albums a year, I’m down to five or six. All of my purchases are made with a purpose.

Some of it is music I can’t find on Tidal or Qobuz. The British classical label Hyperion Records doesn’t appear to offer any of its content through streaming services. In the past few months, there have been a few Hyperion releases I really wanted, including a two-piano arrangement of The Rite of Spring played by Marc-André Hamelin and Leif Ove Andsnes. I was happy to spring for 24/96 downloads of that record, and a couple of other recent Hyperion albums.

A musical highlight of 2018 for my much better half and me was a concert at last summer’s Toronto Jazz Festival by The Bad Plus. The jazz power trio was touring its new album, Never Stop II, the first featuring pianist Orrin Evans, who replaced Ethan Iverson in early 2017. It was a fantastic show, and I definitely wanted the album. But the band appears to no longer have a recording contract, and its new album is available only on the band’s website (www.thebadplus.com). Again, I was happy to pay for the album, and I’ve played it over and over.

The Bad Plus

The Bad Plus

My other three downloads are available through streaming -- and in hi-rez. The Punch Brothers’ All Ashore, Brad Mehldau’s After Bach, and Chris Thile & Brad Mehldau are all from the same label, Nonesuch. I knew I wanted these albums in my collection, but I waited to buy them until Nonesuch had a one-day 50%-off sale.

However, I’m listening to more music, and finding more new music, than ever. On Tidal and Qobuz, I’ve designated hundreds of albums as favorites. I’ve listened to some of them several times, but others only once (though I want to come back to them). And there are many that I haven’t listened to at all; after reading or hearing about them, I file them under Favorites.

Interestingly, my burgeoning Favorites lists on Tidal and Qobuz make me appreciate the urge to collect. With so much choice, it’s nice to have a collection of music that’s just yours.

When I interviewed David Sax, author of The Revenge of Analog: Real Things and Why They Matter, for the May 2017 issue of WiFi HiFi, he compared streaming to “a Vegas buffet. You don’t really want to eat anything; you just want something sort of smaller.” For many music lovers, including Sax, that “something sort of smaller” is a carefully curated collection of LPs. For others, it’s a personal collection of digital files, just as carefully curated.

Understood that way, I don’t think downloads are dead. While downloads will have a diminishing role in most people’s musical lives, they’ll still have a place -- and a very personal one.

. . . Gordon Brockhouse